Today Rith, my language teacher, and I went visit Wat Ang Krapeu, a popular pagoda during the Buddhist holiday of Pchum Ben. Together with Rith's extended family and friends (about 15 people), we traveled for about hour outside of Phnom Penh to visit this wat, which in the rainy monsoon season is mostly surrounded by water stretching out to the distant hills. The name of Wat Ang Krapeu refers to the crocodiles (

krapeu is Khmer for crocodile) that used to live in the area.

Pchum Ben is one of two major Buddhist festivals each year in Cambodia, the other being Khmer New Year. Pchum Ben, celebrated in different forms and with different names throughout Asia, is the official end of the three-month rainy season monastic retreat, a tradition begun by the Buddha himself 2500 years ago, during which monks are expected to study more intensely and follow a more strict discipline in their home wat. Pchum Ben, celebrated over a period of fifteen days, actually has little to do with the monastic retreat. The fifteen days begin with Autumn Moon Festival, which is more known as a Chinese holiday and even in Cambodia it is traditional to eat Chinese moon cakes.

During Pchum Ben, many Cambodian Buddhists believe that the spirits (hungry ghosts or hell-beings) of their ancestors, especially those who have accumulated negative karma, come out during the early morning hours, usually from 3:00 AM until sunrise. So at 3:00 AM all across Cambodia, the wats are filled with people. Most buy or have made for themselves plates of rice rolled into small balls, which are used to feed the ghosts and hell-beings which come out during the night. The believers, with candles in hand, then circumambulate (very slowly, because there are often lots and lots of people) the

vihear (main temple building of the wat) while simultaneously throwing the rice balls towards the walls of the temple. In case you're wondering, this also happens to be a good deal of fun; in fact, I have rarely seen people having so much fun at 3:00 AM.

Pchum Ben is also much more than these early morning rituals. During the daytime, many more lay Buddhists go to the wats during the day to listen to Buddhist teachings, pray, or offer food to the monks. Because Pchum Ben is generally more about honoring one's ancestors than practicing Buddhism, the aim of all these activities is to transfer karmic merit to one's deceased relatives. Women tend to dress up in a traditional Khmer dress and white top when they visit the wat during Pchum Ben (as dressed up as they would be for a wedding or another formal occasion), which is interpreted as a gesture of respect. The wats themselves also have a great deal more decorations during this time.

Wat Ang Krapeu, like nearly all wats in Cambodia, was rebuilt after the Khmer Rouge destruction, so it is architectually in the same mould of most other wats. However, the large concrete elephant tusks shown above were new for me, and those who I talked to about them didn't seem to understand them either.

Another interesting element to the wat is the prescence of this small Chinese altar, unusually for a Khmer wat, in a small temple behind the main vihear. Although these pictures were all taken after most of the people left to go home, Wat Ang Krapeu was indeed very crowded today. Some of the people were making ritual minature sand mountains on the grounds of the wat, others were offering and preparing food for the

sangha, while others were seeking the advice of a monk in the vihear. A festive, though respectful, atmosphere pervaded the wat, and the well-dressed lay believers, young and old alike, were engaging in just about the full range of Khmer religious activities.

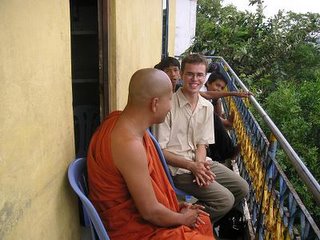

Rith's family and I went to a small temple on the edge of wat to visit a

tsun ji, the closest equilvalent of a nun in the Khmer tradition, who was also a medium (

gru boramey). Mediums and trance states are outside the realm of Buddhism and are specifically prohibited in the

vinaya, but their popularity in Cambodia is widespread. In short, a gru boramey is a medium for any number of spirits, usually those of kings or accomplised acsetics, who manifest in the gru boramey when he or she calls the spirit to enter their body. When the spirit in present in them, they manifest the characterestics, including the preferred language, of the spirit.

The tsun ji we visited, a relative of Rith's, is a gru boramey who manifests the spirit of Jayavarman VII, a famous Angkorian king. Rith's mother was looking for advice, so she sought out this medium to for help. After presenting the medium with some symbolic gifts, she (the medium) began to make incantations in Sanskrit to call the spirit to enter her body. After a period of more chanting and ritual, the spirit entered her (apparently) and her personality changed completely. She also began to speak in Thai, a language that the gru boramey doesn't know when the spirit is not inhabiting her body. Then Rith's mother, Rith, the spirit inhabiting the medium, and a monk the spirit was talking to (this monk we couldn't see or hear, but we could tell the spirit was talking to a monk), began to have a lively conversation. For the most part I could follow what was going on, as Rith would occasionally translate and clarify things for me, except when the spirit began to speak in Thai!

Gru boramey have a complex relationship with mainstream Theravada Buddhism, because although they are generally prohibited from practicing in wats, many still do and even some monks are known to be gru boramey. Gru boramey are also generally dedicated practioners of the Buddhist precepts and are supportive of the sangha, and nearly all of them give everything that people offer to them directly to the wat. Taking this into account, it is hard to say how they fit into the context of a wider Buddhist tradition, if they do at all, but it is safe to say that Cambodia is the only country where gru boramey and Theravada Buddhism co-exist to such a great extent.

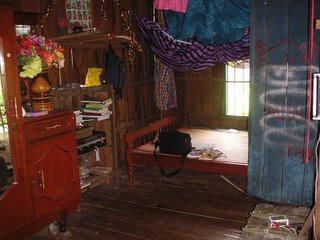

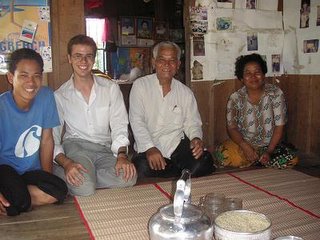

After the spirit left the gru boramey, we were all able to have a nice conversation and lunch together in her small home. A while later, I was by chance able to meet some young orphans at the wat and hear them perform some

pin peat music that they had been studying. I am continually amazed by these kinds of experiences that I am having in Cambodia, and while some of them are certainly more foriegn to me than others, I am very grateful for the chance to have them.

They asked me to give a speech, though I admit I was at a loss at what to say.

They asked me to give a speech, though I admit I was at a loss at what to say.

Today Rith, my language teacher, and I went visit Wat Ang Krapeu, a popular pagoda during the Buddhist holiday of Pchum Ben. Together with Rith's extended family and friends (about 15 people), we traveled for about hour outside of Phnom Penh to visit this wat, which in the rainy monsoon season is mostly surrounded by water stretching out to the distant hills. The name of Wat Ang Krapeu refers to the crocodiles (krapeu is Khmer for crocodile) that used to live in the area.

Today Rith, my language teacher, and I went visit Wat Ang Krapeu, a popular pagoda during the Buddhist holiday of Pchum Ben. Together with Rith's extended family and friends (about 15 people), we traveled for about hour outside of Phnom Penh to visit this wat, which in the rainy monsoon season is mostly surrounded by water stretching out to the distant hills. The name of Wat Ang Krapeu refers to the crocodiles (krapeu is Khmer for crocodile) that used to live in the area.