Reflections on Cambodia, Buddhism and Music

Tuesday, August 30, 2005

High-Context, Low-Context

Well, to get back to the question of respect, I notice that Khmer people use pretty respectful language around me, which defines the context of our relationship. I'm pretty used to our American "low-context" society, where we use about the same language with everybody and how we act is often based more on our individual disposition than the particular context we are in. So it is occasionally frustrating that it is nearly impossible to have "normal" social relationships with other Cambodians--that is, it is hard to be on equal terms with them. And because I am almost always in the dominant position of power, it can be hard for me realize the societal context that I'm in.

Of course, I have a lot of "power" in American society, but I was not made aware of it until coming here. And I can hardly complain about it, both because I want to respect the culture I'm living in and because I can appreciate what it's like to be on the other side of the hierarchy. Yet I realize that my American habits and inability to understand the "high-context" nature of Cambodian society will be an ever-present source of learning and frustration.

After I finished that paragraph, a young boy came up to me and asked me if he could shine my shoes. He explained that tomorrow he needed money to go to school. Whether or not this was true, it saddens me greatly to see children having to work or beg all hours of the day. But to express hope at the end of this post, I visited a gallery opening today of probably the first arts school in Cambodia (Reyum Arts School, www.reyum.org) that encourages creative expression through painting, drawing, and other media. Because schools are so overcrowded in Cambodia, kids can only go to either in the morning or the afternoon, and Reyum gives kids not only a safe environment so they don't have be unstructured and unsupervised on the street for much of the day, but also a chance to create and learn with their peers and prepare for a future vocation and a lifelong love of art. It makes me truly happy to see such positive action and the beautiful results of such action.

Monday, August 29, 2005

A Breath of Fresh Air

Today I made my first trip to the Cambodian countryside to visit two smoat masters in Konpong Speu province. Smoat is a very soulful style of singing, almost chant-like, that is used in Buddhist funeral ceremonies. The songs are often poetic retelling of Buddhist stories, and usually are morally or spiritually didactic. A common subject of smoat music is jataka, Buddhist stories, either canonical or apocryphal and unique to Khmer culture, that recount the Buddha's previous lives before he attained enlightenment. There are over 547 jataka in the Pali Canon, and many more have circulated in Cambodia, and most of them recount the lives of virtuous animals and have a very playful character, although they generally end with the main character dying. The most commonly heard are the last ten lives of the Buddha, and even more so the Buddha's final life before he was born as the Indian prince Siddartha Gautama. In his next-to-last rebirth, the Buddha took the form of Prince Vessantara, who represents the perfection of generousity by giving away his possesions, his land, his country, his wife, his children, etc., until he literally gives away his heart. It's a remarkable little story with lots of delicious details, including a greedy old man who eats too much and, just like you or I would in a similar situation, explodes. But getting back to the music at hand, smoat is particularly beautiful style of singing, with long phrases and characteristic ornamentation.

Sambor and I drove for about an hour and a half to reach the masters, after making it through some muddy roads and several detours. The countryside, filled with rice paddies of a brilliant green color and tall, slender palm trees, is beautiful. It was so refreshing to be out of the city, where the pollution makes it difficult to breathe, and be closer to nature. The poverty is also more apparent, but in a different, and less jarring, way than in the city. We finally arrived at where the smoat class was being held, at a house, on stilts to avert flood damage, in a small village. We were greeted by one of the masters and some of the students, who led us up the stairs and into the house, where there were about twenty students sitting on the floor. After traditional greetings, we all took a seat and introduced each other.

The two masters, one man and one woman, have very fine voices and it was great to meet them in person after listening to their recordings. The man began his study of smoat when he was fifteen years old and a novice monk at a Buddhist wat. He is now considered one of the foremost masters of the art. The woman was a bit younger, and is believed to suffer from hysterical blindness, a psycho-somatic illness that afflicts a certain number of older Cambodian women who were forced to watch the execution of their husbands during the Khmer Rouge era. They are both very kind teachers, and I feel fortunate to have had the chance to meet them.

We all talked for a couple hours about smoat, and I learned a lot from the exchange. Several of the students, who had remarkable voices, also shared some of their skills. They were interested in opera, but through some confusion in translation, I thought they meant throatsinging, so I shared some of that before I sang some of the very limited German opera I know. All things considered, it did feel a little weird for me to be the only medium through which they had ever heard Tuvan throatsinging or German arias. But the sense of exchange was powerful for both me and them, and they repeated that I would be very welcome to stay in their community, perhaps at the local wat, and study smoat. I don't know if will decide to live in Konpong Speu and study this wonderful form of music, but I am very happy to have this experience and to meet such welcoming people.

Sambor and I then went to visit the local wat, which sits on top of the only hill for miles. As such, it has a gorgeous view of the surrounding countryside. After two weeks in crowded, congested cities, the pure air and the peacefulness were a welcome relief. The wat was very simple, but the trees and majestic silence were duly inspiring. I hope very mcuh that I will return. Here's a picture of the view from the top:

Below is another image of the view:

After I captured this image, it realized that the view really reminded me of a series of paintings by Cezanne of Mont St. Victoire.

Sunday, August 28, 2005

New and Depressing Things

There are many victims of land mines in Phnom Penh--those that have lost limbs, mobility, livelihood and sometimes even half their face from the perennial results of war from decades earlier. And their are just as many who are handicapped or horrifically disfigured from illnesses and accidents unrelated to war, but because of the medical standards of the country, they are unable to find meaningful or affordable treatment. Young men arrive from the countryside and find no work in the city. Mothers send their children out onto the street with their babies to beg for money. And street children who truly have no home struggle to survive by selling a few newspapers or bootlegged books.

Moreover, even their own government is trying to uproot the poor from their homes and their livelihoods. The Tonle Bassac community where I visited four masters and their music classes is one example. The community is named because of the theater that used to exist there, which was likely burned down by the CPP (Cambodian People's People, the current ruling party of Cambodia, headed by Prime Minister Hun Sen, who is widely disliked among the Khmer for his authoritarian rule, the corruption of his administration, and his disinterest in helping Cambodians who are not rich businessmen). The community lives in fear of eviction because developers and the government officials who will profit from such development want the slum converted in a shopping mall.

For me, this is the kind of story that I read about happening but could never really understand what was going on. But now that I know the people that it affects so deeply, and have witnessed the strength of their resolve in creating a revival of the arts in their community, the situation pains me much more. Today, UN officials visited the community and interviewed Ki Mum and her students, whom I had visited just days before. Through the interviews it became apparent that the government had been threatening the residents of the Tonle Bassac to move elsewhere or their community would be burned down or bulldozed without advance notice. And the threats are not empty because the community has been a victim of arson by the government before. Furthermore, the government is now threatening legal action against the members of the community because it alledges that the 800 fingerprints the residents collected to certify the joint complaint they filed were fake. This is truly a deplorable situation, and is certainly one of the most outrageous examples of economic cruelty I have ever heard of.

All this makes me wonder why I choose to just study music and Buddhism during my time here. Shouldn't I be working to improve the material conditions of the people in Cambodia? Well, shouldn't you? If you have the financial means, there are many NGO's that are doing excellent work in health care, human rights, AIDS, women's rights and other areas in Phnom Penh and I am sure they would appreciate your support. And not just in Cambodia--a comparatively small sum of American money goes a long way in developing countries, whether it be to buy mosquito nets, to fund education about sexually transmitted diseases, or to help bring justice to issues of human rights. I, too, hope that I can find a way to meaningfully contribute to the material well-being of Cambodians.

However, my main intention in my time here is to look at Cambodia not as a country of problems, but as one whose rich musical, spiritual and artistic traditions have a great deal to teach the world. In a post-genocide society, restoring faith in one's culture, religion and traditions goes a long way toward promoting emotional and spiritual health. And while I know my impact me indeed be small, I sincerely hope that I can always remember to make this my intention during my time here. I love this country, its people, its language, its spiritual values and its arts traditions, and I want to make sure these treasures are accessible to the Cambodian people and may be a point of pride to the world at large.

Saturday, August 27, 2005

One-string Wonder

I've been teaching myself to play khsae dieu (see above), a one-string Khmer instrument with a particularly delicate and quiet tone. The instrument was once heard often in the countryside in the evenings, when elderly men would quietly play the instrument before retiring to bed. Although it only has one string, the instrument can produce complete scales through the use of overtones and pitch-bending. The picture below shows me attempting to play it.

The left hand stops the string against the wooden shaft to generate different pitches, while the ring finger of the right hand plucks the string. However, many more pitches can be generated through two special techniques in the right hand. The first is simply to push down on the shaft with the right little finger, which increases the tension on the string and thus raises the pitch as much as a fourth. The other technique is to gently touch the right forefinger to the string while plucking as usual with the ring finger. If done at the right places along the string, a particular overtone is isolated (the octave, the fifth, the second octave, the third, the fifth, etc.), allowing for a full range of three octaves and all the tones in between. When the overtone is isolated in this manner, the khsae dieu has a very pure and beautiful tone, unlike almost any other string instrument. The only other similar instrument I've heard is the Vietnamese dan bau, another one-string instrument that uses overtone isolation.

The khsae dieu is a very enjoyable instrument to play, one that is uniquely Khmer in character. The Ven. Pin Sem, abbot of Wat Bo in Siem Reap (near the Angkor Wat temple complex, northwestern Cambodia), pleaded succesfully with one of the few remaining masters of this instrument to have it taught to the wat to local students. It now looks like there are enough students to pass the instrument and the repertoire associated with it down to the next generation.

I also had my first Khmer lesson today with Rith, a sharp, enthusiastic fellow. His teaching style seems to work well, and today we acted out a scene in a restaurant to practice vocabulary and sentence building. And the lesson has already paid off, because for dinner today I went to a local Khmer eatery (not really a restaurant, more a home that turns into a noodle-serving joint in the evening) and ordered in Khmer. I am planning to go to the local market tomorrow to buy fruits, vegetables, and tofu so that I can cook for myself. I probably won't be saving money this way, as my dinner today was about 63 cents, but it will be more enjoyable and I need to improve my cooking skills.

Friday, August 26, 2005

Settled In

The room where I'm sleeping looks something like this:

I am continuing to practice Khmer on my own, although I am meeting with a teacher tomorrow to arrange some lessons. I am finding it much easier to learn a language in the country where it is spoken, because it can be used all the time. Below is some writing I've been working on (colors inverted just for fun).

On Monday, I plan to make my first trip out of the city to visit the smot masters in Takeo province. In the meantime, I will be helping as much as I can with the CD project, which is a great learning experience for me. It is only now dawning on me that I am going to be spending such a long time in this country, which is both daunting and comforting. I hope that over the next month I will have a much better idea of what I will be focusing on this year.

Thursday, August 25, 2005

A Successful Session

I spent most of the day yesterday at the CLA recording studio, observing a very successful recording session. My official duty was to take pictures forthe liner notes, but the flash drained the batttery after about five pictures. So I mostly was able to listen to some amazing music, watch how Cambodian musicians work, and learn more about the process of recording. The sessions were remarkably problem-free. Apart from some drilling and other construction work happening next door, there was little to worry about in terms of sonic interference. In addition, there were only a few technical difficulties with the recording equipment. But most of all, the musicians, fifteen in all, played almost flawlessly throughout the day, and only a few takes had to be restarted.

The music and musicians had been organized by the master teacher and professor Yun Theara, a enormously talented multi-instrumentalist who has emerged as one of the leading traditional musicians in Cambodia today. Beau, who was supervising the recording process and training the Cambodian studio engineers in the art of microphone placement and levels, was very happy with the results. Although I know only a little about Cambodian music, what I did hear in the studio was some of the best-recorded and well-performed Cambodian music I have ever heard. It's great to see Cambodia's master musicians recording and playing music together at such high levels again.

As I am writing this at an internet cafe in Phnom Penh, I am sitting between two monks who are chatting online or writing emails. I have been reading about the state of Cambodian Buddhism in the post-Democratic Kampuchea (Khmer Rouge) era. I am curious to learn more about the state of the sangha, the vision of the leadership (if indeed they have a vision), and the way contemporary Cambodian Buddhism relates to the arts in the country (if there is indeed any relation). There is always lots to learn!

Four Masters

Sambor, a young Cambodian man who works for CLA, was kind enough to translate for me when meeting with thew masters and their students. We parked the car and walked through the dirt and gravel streets of the community, which mostly consists of corrugated metal and wood homes, with many familky members crowded into each. The poverty heree has no equivalent in the United States, and I have to constantly remind myself that so much of humanity lives on as little as these people do. And it makes it all the more remarkable that this is the focus of a renewal of the arts in Cambodia.

Sambor and I first went to visit Tep Mori's pin peat class. It was held in a tile-floored room, and there were about a dozen young students sitting on the floor with their instruments. Pin peat is a form of court music, used for formal ceremonies as well as certain dances in Cambodia. The ensemble typically consists of several large drums (sko thom), three or four wooden xylophones (roneat), and several circular metallophones (gong). The students were mostly girls, between nine and fifteen years old, and they played together extremely well. All the songs they know they learned by rote memorization from their teacher, as no notation system is widely used in Cambodia. When I asked them what they enjoyed most about studying traditional music, the students replied that they got a chance to learn "precious knowledge"about their culture from great teachers. I think all too often I have taken for granted what I have learned in school, but the spirit of these students reminded me how precious it is to learn. Tep Mori had clearly trained her young students very well, and she remarked how important it is to pass down the musical traditions to the next generation.

We then headed over to Kong Nai's house. Blind from the age of four, Kong Nai began to study chapei dong veng when he was thirteen at the behest of his uncle, who knew music would be a possible profession for someone who had lost his sight. His musical gifts are apparent in his dynamic chapei playing and in his soulful, improvised song. He's kind of a Cambodian blues man, and he often commands a lively social scene on his front porch. Kong Nai talked about his music for a little while, though it was hard to get an idea of how his class was run. One the whole, however, he displayed a much more casual and easy-going attitude than the other masters.

Sambor and I then went to visit Ki Mum's yike class, which was held on the third floor of an appartment building in dangerously poor repair. The class had about twenty-five students, with an even mix of girls and boys, ranging in age from nine to eighteen. Divided into groups of instrumentalists, singers, and dancers, the class performed a lengthly and complex piece. They sang and danced with vibrant enthusiasm, and I realized how wonderful it was to have young people dedicated to learning such ancient music. They studied six days a week to learn the songs and dances. I don't know enough about dance to write about it coherently, but I observe that Cambodian dance is very grounded in approach and prominently features highly stylized hand gestures, to the extent that the hands are almost always the center of attention. The more time I spend around this music and dance, the more I realize how much I love it.

The last class we visited was that of Ieng Sithul, a master teacher of wedding music. Because he is currently performing in the United States, his class was taught by two assistants, including Ieng's wife. This was the largest class I visited, with about forty students. It was also the most disciplined class, and I was deeply touched when they all stood up as we entered the room, palms joined in the traditional Khmer greeting. Wedding music has a particularly joyful sound, and the students played and sang with evident mirth and concentration. These were truly some of the best young musicians I had ever seen, and I was equally impressed with their dancing. For such a young program, the students seemed to be exceptionally well-trained.

After I had the chance to ask them questions about their art, the students asked me why I had come all the way to Cambodia to study Khmer music for a year. This was the first time I really had to think about this question, and the first time I had an experience that really showed me the answer. Music in Cambodia is not separate from the other arts, religions and the culture in general. Although the continuity of Cambodia's musical tradition was severely damaged by the Khmer Rouge and remains under threat by a lessening interest in traditional arts among the youth, I cannot hope to understand the culture withou understanding the music, and vice versa. When I come back, I will not know enough to really teach about Khmer music, but I think I will get a sense of how intertwined music and culture are, and how important music is to a healthy sense of identity and meaning in a country whose tragic history rendered life increasingly meaningless and painful. Music redeems us, and it challenges us to continually create new life and light where there was only death and darkness before.

Wednesday, August 24, 2005

A Change in Pace

Parker, Beau and I went to visit the Buddhist Institute. The library they have is a fantastic place to study and do research, and I have inquired as to whether classes are available and if I might find support for my project there. The building itself is quite handsome, although there is a gigantic casino located right next door.

Today, I a m going to visit four masters in CLA's program and then head over to the studio to help out with the recording session. Yesterday, when meeting with Yun Theara, the Cambodian multi-instrumentalist and professor of the Royal University of Fine Arts, it looked like I would have to play bass on the album, but fortunately it looks like my role will be to take pictures for the liner notes. I'll try to report back after today.

Tuesday, August 23, 2005

A Restful Change in Plans

The time passed relatively quickly. One thing I've noticed about life in Cambodia is that people never seem to be bored. When there's nothing to do, even for hours on end, this is no cause for complaint. Rest is appreciated, especially in such hot weather and with hard work to do.

Today, Parker and I are planning on visiting the Buddhist Institute in Phnom Penh, which offers graduate study of Buddhist philosophy. And tomorrow it looks like I'll have a chance to meet four of the CLA masters in the Bassac community, including Tep Mori, Kong Nai, Kea Mum and Im Hito--we'll see!

Conversation and Collage

I am slowly beginning to get a sense of what I'm going to be doing this year. Yesterday, I took a walk along the river (the Tonle Sap) and had a chance to talk with many Cambodians who wanted to practice their English. I also got to practice my limited Khmer with them. It's great to meet new people in this way, even when our respective language skills makes it hard to communicate. But I am continually amazed and overjoyed by the friendliness of the Cambodian people, even in a hectic, modern city like Phnom Penh.

Today, Parker and I went to buy some Khmer newspapers and magazines in order to make collages with them. Making art is both calming and centering, and I feel more balanced and ready to live more carefully after doing so.

Tomorrow, I am going to visit Tep Mori's pin peat class in the Bassac community (more on this after I tomorrow). I actually briefly visited her on the first day I arrived, when we were on our way to visit Kong Nai, a blind chapei (Cambodian long-necked lute) player and improvisational singer. He's known as a sort of Cambodian bard, whose words and music express the popular sentiments on the people as well as his own personal flair. CLA is now working to produce an album of his music, part of an upcoming release of three albums of Cambodian music on the CLA label. It has been great to watch this project unfold, from meetings with the Thai embassy to secure a printing house in Bangkok to press the CD's to listening to different cuts of Cambodian musicians at the studio. As the project moves further along, I will probably get more involved to make sure everything runs smoothly. It's really exciting to be a part of this organization and I am hoping to learn more about how CLA and World Education work in Cambodia, as well as about the general model for NGO's in developing countries.

Monday, August 22, 2005

Wat Ummalom and Wat Phnom

The stone carvings were especially intricate and complex. The Khmer architectural style is unlike any I have ever seen, reminescent of some Indian Buddhist structures but completely different than the temples in Vietnam. And the symbolism in the art is a rich blend of Buddhist, Brahmanistic (Hindu), and indigeneous Khmer elements. At Wat Ummalom, there are also many stupas (conical Buddhist reliquaries), lingas (phallic representations of the Brahman deity Shiva), and scenes from the Reamker (the Khmer version of the Indian Ramayama epic).

And it was great to see the wat on such a gorgeous day, as it has been raining a lot lately. When it rains in Phnom Penh, it really rains hard, and the streets flood temporarily. Once the rain stops, however, the weather is very pleasant and cool. Because didn't rain today, by noon it was very hot outside.

After seeing Wat Ummalom, I took a walk over to Wat Phnom, which is situated on the only hill in the city. The wat is surrounded by a public park, for both humans and monkeys.

The wat also has many stupas, but is more typically Buddhist in style, and there are even several areas which are devoted to a more Chinese religious theme. The main temple is decorated with scenes from the Buddha's mythological past lives, known as the jataka stories, in which he sacrifices himself for the benefit of other living beings, especially animals. The most famous jataka in Cambodia is that of Prince Vessantara, which is the archetype of generousity in the popular Buddhist tradition. I had never been in a Theravada Buddhist temple before, and I was suprised to both the similarities and differences to Mahayana temples I have visited elsewhere. Wat Phnom does not appear to have many monks, and its function as a wat is mostly ceremonial.

I have a lot to learn about Buddhism in Cambodia, both in terms of understanding how animistic and Brahmanistic elements have been incorporated into the tradition and in terms of understanding how the terror of Democratic Kampuchea (the Khmer Rouge) broke the continuity of Buddhist teaching in Cambodia.

Sunday, August 21, 2005

CLA Studio

The inside of the studio is simple and functional, if a tad disorganized:

And there was a tro sau lying around that I tried to play. It's quite similar to the Chinese erhu, though with a slighter huskier and rougher tone:

While at the studio, I had the chance to listen to some of the recordings they had on file. The quality is excellent, although some recording glitches are still present. Beau burned a CD for me of as sampling of traditional genres. I'm still trying to figure out what kind of music I will pursue study in. At this point, I am particularly interested in smot, a vocal form of funeral music. It may sound morbid to you, but the music is haunting, soulful and meditative, and I am curious to learn more about it.

Saturday, August 20, 2005

Tropical Fruit and Syllabic Writing

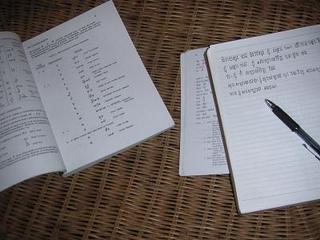

I have also begun to study written Khmer (Cambodian) on my own, starting with consonants:

I have also begun to study written Khmer (Cambodian) on my own, starting with consonants: and moving on to simple sentences:

and moving on to simple sentences: It's difficult, but very satisfying and I hope to find a language teacher soon.

It's difficult, but very satisfying and I hope to find a language teacher soon.

Friday, August 19, 2005

Greetings from Phnom Penh!

Saffron-robed monks can be seen on the sidewalke and the grounds of the temple.

Saffron-robed monks can be seen on the sidewalke and the grounds of the temple.Phnom Penh is a beautiful city, with wide, tree-;oned boulevards and few, if any, tall buildings. There are several rivers that cut through the city as well as several lakes. There are also many wats and other cultural landmarks in the vicinity. I definitely feel like I am a completely different country than Vietnam.

I am basically hanging out with Parker all day for the next few days as he helps orient me to the city, the culture and the work that Cambodian Living Arts (CLA) does. It has not yet dawned on me that I am staying here long-term, but I am slowly getting the hang of it.

Thursday, August 18, 2005

Tran Quoc Pagoda, Part 2

I returned to Tran Quoc Pagoda in the afternoon. There were many more monks and laypeople there this time. In addition, there were two laymen, of whom was Chinese, who were there to help out with the ceremony.

One of them played dan nhi (a Vietnamese version of the Chinese jinghu, a two-string fiddle related to the larger erhu) and a shawm (sona), an extremely loud, wailing oboe-like double-reed horn. The other, who was proficient in classical Chinese, helped with some of the chanting and also played drums. The two men were dressed in black lay robes.

I had a hard time understanding the context of the ceremony. I expected to stay only a short while, but when I left, over three hours later, the ceremony was still going, with no sign of stopping.

I was directed to sit on the tile floor, about twenty feet from the altar. The hall on this level was much more complex than the one downstairs. There were paper pendants and flags hanging everywhere with Chinese characters written on them, and the altar itself was huge, with four or five levels extending back another twenty feet. On the altar were of course the requisite Buddha images but also about a dozen life-size statues of men sitting in Chinese mandarin chairs with long beards and traditional imperial headgear. Upon closer inspection, I realized that one of the figures was King Tran, a medieval monarch of Vietnam who lated abdicated the throne, took on the robes of a monk, eventually becoming a Zen master and an important patriach of Vietnamese Buddhism.

Before the ceremony began, an elderly monk donned formal robes and a silk Chinese crown. He also carried a large staff and stood solemnly in front of the altar. The rest of the monks and the two laymen, sitting behind him in two rows, began to chant and play their instruments. One of the monks had a mircophone that was hooked up to a speaker system that was turned way up, so the chanting was rather loud, especially in a tiled room where most of the materials reflected the sound. And with the wailing shawm and drums, bells, and cymbals played at a high volume, it became extremely loud. But the chanting and the music that accompanied it was beautiful and had a centering quality, and all of the men played together exceptionally well.

The opening chants, sungs from books or from memory, lasted about an hour, at which point my last had fallen asleep and probably were dreaming, though I'm not sure. Then the elderly monk began a complex, esoteric dance before the altar, employing highly stylized mudras (hand gestures) and intricate footwork. Hen then took a carving knife and a red pair of scissors (supposed both remplacement for more expensive ritual items) off the altar and continued his dance with them, as if he was holding a Tibetan bell and vajra.

The monk danced rapidly around the hall, stopping by the walls and pillars to hack off various pieces of paper and cloth imprinted with Chinese characters, which he wound into a ball. The characters were the names of deceased people associated with the temple and this ceremony, I think, was a way of remembering, honoring, and transfering merit to them, and marking the impermanence of all things. The monk held the ball with the knife and scissors, brought it to the altar, bowed low, set the ball on fire, and continued the dance around the hall while holding this ball of fire, which he eventually placed in a bucket of water at the front of the altar.

Midway through the ceremony, a candle accidently set a paper flag ablaze, which prompted several monks to set about trying to put the fire out. At this point, I realized that there were no smoke alarms in this temple! Occasionally the elderly monk would lead us in a quick-paced circumambulation of the altar as a way of further honoring the dead.

A little after six in the evening, I realized I needed to leave to meet a friend, but the ceremony (and the deafening music) was still going strong after three hours. I quietly bowed and left, hoping that I would return one day to talk to the monks again.

Although I experienced only a small part of Vietnam, I am thankful that I had the chance to experience that part deeply and meaningully. Everyone I met was warm and friendly, and many wanted to talk to me. Earlier in this blog, I mentioned how I thought that joyful and honest interactions with strangers were a good measure of the health of a society. And while I don't know to what extent the Vietnamese wlecomed visitors from within their own country, I did always feel welcomed here, in a way that went beyond simple means of securing their income from my wallet. For example, I don't recall the same friendliness in China or Japan, and only on occasion in the States. As I was writing this on the plane to Cambodia, I am sad to leave but very excited to settle more long-term in a new culture.

To all of you who read and don't read this blog, I extend my best wishes to you and I would love to hear from you anytime.

Wednesday, August 17, 2005

Tran Quoc Pagoda, Part 1

The outside of the temple is rather dull and gray in color, but the second and third levels of the facade has ornate Buddhist images. I walked into the doorway, and an elderly woman, crouching in a corner, directed me inside. I removed my shoes and entered into the lower level Buddha hall, where three monks and about six lay believers were chanting and bowing. The style of the musical accompaniment (very vigorous drum and cymbal work) and the motifs on the altar (lots of colors, ornate Buddhist imagery) gave the temple a Tibetan feel. And monks were wearing very formal ritual robes--this was not a Chien (Zen) temple! I joined them until the ceremony ended.

Afterwards, I began to talk with some of the lay believers there, some of whom spoke English. They seemed to appreciate that someone was interested in their religion. One of them even insisted on giving me an apple and an Asian pear (which I think she snatched off the altar) as a "souvenir." I tried to refuse, but they insisted. I was getting ready to leave when the monks led me in to their kitchen, sat me down at the table and served me some tea. I was suprised and delighted by this unexpected hospitality, and appreciated the chance to be able to meet some of the sangha in Vietnam.

We attempted to communicate through hand gestures for a while, but one of the monks slowly began to reveal his English skills. We talked about our families--some of them had family in America--and when they couldn't quite say what were trying to say, they wrote it down on a piece of paper and we worked it out together. When we began to talk about Buddhism, I discovered that some of them knew Chinese, and most of the extremely limited Mandarin and Chinese Characters I know are Buddhist-related. I had never really had a useful conversation in Mandarin before, and it was a pleasant suprise to have it in Vietnam. My tea cup was always kept full!

Later on, the elderly woman who was at the doorway of the temple came up to me and began to speak in French. She was 82 years old (I had originally thought 92, but I mixed quatre-vingt-deux and quatre-vingt-douze!) and had studied French in the eight years she attended school during the colonial era. She had a consistent and beautiful smile on her face, and I feel fortunate that we shared a common language.

One of the monks, Thich Giac Lam, gave me his email address and asked for mine. I didn't hesitate, but I was slightly suprised because a) the temple had bats in it b) I didn't see a laptop under his robes and c) I wouldn't know how to email in Vietnamese. However, I could understand because a) the bats weren't that big b) Thich Giac Lam did indeed have a cell phone under his robes and c) the abbot of the temple took cell calls during ceremonies.

We got to talking about Guan Shi Yin Bodhisattva, when one of the monks disappeared through a door and came back with a small ceramic image of her (Guan Yin). Again, they insisted tthat accept it as a souvenir (although they explained that was infact from China, and the colored strings inside were of special importance. We then shared some of the mantras we knew associated with Guan Shi Yin pu sa.

The monks asked that I return the next day at 3:00 PM to see the drums and bells upstairs. We then bowed and said goodbye ("nam mo a mi ba phat," except the elderly woman, who said, "Au revoir!").

I was out of clothes, so the next morning I perused some shops to obtain a couple of shirts, a pair of shoes, and trousers. Again, it was a delight to just do simple everyday things in Saigon.

(continued above in Tran Quoc Pagoda, Part 2)

Tuesday, August 16, 2005

Four Pagodas in Saigon

The temple is a real community center, with little kids and elderly alike just hanging out on the premises, seeking refuge from the midday heat in the shade of its trees. And those chanting parked their motorbikes only a few meters from where they now stand barefoot, with hands in prayer. The horns of the street traffic are wholly mixed with the beautiful sounds of the chanting. A layman, meditating with his prayer beads, eyes closed in concentration, invited the large hanging bell to sound at regular intervals.

When the weather is this hot and humid, thinking comes a little slower and it is easier to relax. There are so many new smells here. Even the incense is different, and in already polluted air is takes on new dimensions. Humid, warm air itself feels a certain way in the nostrils.

This morning I visited three other temples, each of which had a distinct character. The second temple I visited seemed deserted at first, as I could hear loud chanting but couldn't tell where it was coming from. I walked towards the rear of the compound and a woman directed me upstairs to where a group of about twenty monks and fifty laypeople were chanting in a large, open-sided hall. I went to the back and sat down next to a young man who shared his chanting book with me. I was eventually able to follow along in the Vietnamese text, but I didn't dare actuallt chant!

It was a beautiful temple, almost French in style, but with many Sino-Vietnamese elements as well. Although Buddhism came to Vietnam mostly from China, the chanting style is markedly different, and of course even the Buddhist mantras (sacred syllables) are pronouced differently (nam mo a mhi pa phat). Occasionally a particular mantra in the chanting will remind of something I've heard in Chinese, but the similarity ends there. It is so refreshing to be in a new Buddhist culture!

At the last temple I visited (the third temple actually was deserted, unlike the second), which was decidedly Chinese in style (it was built by ethnic Chinese), I went to the back of the main hall where I heard some chanting. I was unsure of the occasion, but the familial bonds between those attending made it seem like a memorial observance. I didn't intend to crash a funeral! But I met another young man there, in his late twenties, by the name of Dui. He spoke excellent English and we discussed meditation practice at length. Hen graciously showed me downstairs and explained a series of pieces of Vietnamese Chien (Zen) calligraphy. It was really wonderful to meet someone who shared such interest and experience in the Buddhadharma from another country. A practicioner of Pure Land Buddhism, he also clearly understand the connections between the various Buddhist schools, especially Chien. And despite our different cultural backgrounds, we were able to communicate in the language of Mahayana Buddhism and when it came time to part, it came naturally to use the universal Buddhist gesture (gassho in Japanese), bow to one another and say "Na Mo Amitabha Buddha," which replaces "Hello," "Goodbye," "Thank you," and "You're welcome" in Buddhist community life.

At all of the temples I visited, after the service ended, a relaxed atmosphere pervaded the pagoda, and everyone takes time to chat with one another or ask questions of the sangha. Another thing that struck me at the places I visited was that I saw barely any tourists, unlike other parts of town. I only wish I could stay longer in Vietnam and learn and experience more of its fascinating and endearing Buddhist tradtion.

Monday, August 15, 2005

Good Morning, Vietnam

I woke up this morning in Ho Chi Minh City, and turned to the window of my hotel room to check out the view. Well, it's nothing spectacular, but I'm happy to have made it over here. A harrowing taxi ride gave me plenty of excitement last night, but it was also great to see the city by night, when the air is a little cooler. Saigon reminds me of parts of Chinese cities, and the traffic is equally confusing, even at 12:30 AM. I won't say any more because I've seen so little. After today, hopefully I'll have a different picture of the city.

Beautiful Clouds in Korea

I must confess that I love long plane flights. I enjoy the opportunity to sit in one spot (apart from getting up to go to the bathroom every hour) and just focus on reading. I'm in the middle of an admirably good book, "The Gods Drink Whiskey," which chronicles a year spent in Cambodia by a young Chicagoan professor of Buddhism. Although unsettling at times, his reflections on his experiences in Phnom Penh reveal the complexities of life there more than an objective text ever could. And as much his opinions and observations challenge my preconceptions, his tone is warm and endearing, and it puts the fears I have of living in Cambodia in a better perspective.

Because I received a vegan meal on the plane, one of the flight attendants knew my (sur)name and proceeded to call me "Mr. Walker" for the rest of the flight. This I found rather amusing but reminded me of the unexpected kindness we receive from people we only see once in our lives. A couple of months ago, a friend and I discussed such moments that occur in our everyday lives, where we interact with total strangers, like bus drivers, waiters, clerks, shopkeepers, or just people on the street, who greet us warmly and with kindness without expecting anything in return. And when we, too, reach out with kindness in such momentary and singular relationships, then we are suprised by the enduring good-heartedness of others. These encounters, however brief and seemingly inconsequential, are vital to a healthy society. Of course, in urban settings we cannot trust others so easily, a fact I am sure to encounter in Saigon and Phnom Penh. But when there is warmth and honesty between strangers, then human life becomes real again.

I'm soon to be boarding a plane to Ho Chi Minh City, where the weather will be much hotter. Even though I haven't arrived in Vietnam, it is truly exciting to be on the other side of world, and I am ever thankful to all of you that have made this adventure possible for me. Best wishes to all.

Saturday, August 13, 2005

And He's Off

I'm going to Cambodia as an intern for Cambodian Living Arts--a division of World Education Fund-- which works to help preserve and reinvigorate traditional Cambodian performing arts. I'm not entirely sure what I'm going to be doing there at the moment, but I expect to study the Khmer language, study a Cambodian instrument and/or musical genre, and conduct some research on particular aspect of the connection between religion and music education in Cambodia.

Over the past few days I have been packing and preparing to leave. It's an interesting exercise to consider which items are essential for a trip and which are not. As it turns out, very littleis essential, and part of the joy of leaving home is findinga a new set of material expectations--that is, finding out how little we actually need.

It's been harder to say goodbye to those who I won't be seeing for a while. But I've noticed that when people realize that they won't see each other the next day, their thoughts are more sincere and more honest-- this is something I've really appreciated lately.

I hope that with this blog I will be to share my experiences with all of you. Please also email me if you have questions or would like to hear more.

Last Ride on BART

I don't try to listen with my ears; the heart knows better. The heart knows my mistakes and their mistakes, and it forgives. The heart does not say much, so I listen to its listening. When I pay attention to the heart, the thoughts of the mind don't matter so much. I laugh at myself for the silly things I worry about.

I enjoy feeling my two feet on the floor--to touch the Earth, even on a moving train, fills me with peace. And I ask myself, "Am listening? Am I listening? Am I listening?" And I ask myself again, "Who's listening?"

Who, indeed, is listening? Who is it that is sitting on this train? I have no idea who I am, how I got here or where I'm going or who this "I" is. And that's okay, for the most part. To not know such things confuses me, amazes me and fills me with wonder. To not know turns me inside-out, but it also opens me, frees me. And in a moment of stillness, where sound and listener and listening merge as one, it's okay. It's really quite okay not to know who I am or where I came from. It's really quite okay just to sit here on this BART train and let wonder open into wonder.

Saturday, August 06, 2005

Living in God's House

Good morning! This summer I lived at Cameron House as part of the summer staff, where I worked as the coordinator for the 3rd and 4th grade department of the Cameron Ventures Program. This year, our department was blessed with ten wonderful leaders and over thirty highly energetic kids.

I graduated from high school in

When I was in high school, I never thought I would end up attending a Christian church, much less working at a place like Cameron House. As a Buddhist, I never had much interest in the Christian faith of my ancestors. I found spiritual fulfillment in the Buddhist tradition of meditation and mindfulness; I had little interest in Christianity.

However, my experience at PCC changed my view. This church introduced me to an open-minded, socially aware, and justice-seeking model of spirituality which really appealed to me. I don't mean to say that I am now less of a Buddhist than before, but I now feel comfortable living with the two religions side by side in my heart.

And so, today I'd like to speak about my experience this summer in terms of what it means to live in God's house. One meaning of what it is to live in God's house is simply living in a Christian community, a community where we make a conscious and explicit commitment to live honestly before God. To live honestly means that we take responsibility for all of our actions, words and attitudes, and to live before God means to live humbly, in respect and wonder. I'd lived in other spiritual communities before, but I'd never lived in a Christian community before coming to Cameron House. I am not without my qualms about Christianity—about evangelism, for instance—and I don't hesitate to say that I would probably feel uncomfortable in many other Christian congregations in this country. But there are aspects of the Christian life at Cameron House that I have come to appreciate very much.

At Cameron House's youth programs, we work to create an environment that balances and fosters physical, mental, social and spiritual development. These four aspects of growth are outlined in the Gospel of Luke, and the expectation is that we model our lives and our development on that of Christ. So much of our media-saturated, hyped-up, heart-broken and suffering world lacks this principle of balance, and our children are not encouraged to grow into their full potential, especially in the spiritual realm.

My time with the kids and high school leaders this summer gave me the chance to encourage their balanced development by working on devotions—spiritual lessons—for the kids and working with the leaders to develop creative and meaningful devotions of their own. I encountered a fair amount of resistance, from the kids, from the leaders, and even from myself, in making these devotions a part of every day. And it forced me to step away from my own perspective and get into the heads of the kids and youth, and see what was meaningful and relevant—spiritually relevant—to them.

Let me offer you an example. A couple of weeks ago, my department was struggling, and the problems were not with the kids, but between my leaders and me. In the end, everything worked out, and to the credit of my leaders, they were able to transform their negative actions into positive lessons for themselves, for me, and for the kids. They accomplished this by creating devotions that spoke to the choices they had made and the lessons they had learned, and I was impressed and moved by their sincerity and thoughtfulness. This sort of transformation is, in my eyes, the essence of the Christian life, that our unwholesome thoughts and deeds may be transformed into what is wholesome and good, through our will and that of God. And I am thankful that we worked out our mistakes in the context of a Christian community, because it was our shared life in God's house that made everything possible.

However, beyond the simple fact of living in a Christian community, there is a further meaning of what it means to live in God's house that I learned about over the summer. For me, God’s house is the wealth of peace, joy and contentment that is available—through the grace of God—in the present moment. To live in God’s house means to live in gratefulness—mindfully, lovingly, slowly but dearly—so that the wonder of life, the wonder of being alive, is fully available to us. The door to God’s house is always open—it is only through our self-centered wills and desires that we cannot find it.

I cannot live this way very well. I find it difficult to slow down and truly appreciate the people who are around me. It’s hard to for me to remember to live mindfully, to live humbly, in wonder. Usually I’m carried away by worries about the past or the future or simply desires and emotions in the present—I rarely can just take a breath and appreciate the whole breath, or listen without judgment to every word someone is saying. But this summer I have learned that when I do take the time to enter the present moment, offer thanks for what I am blessed with, and let God take me in to God’s house, then everything works out better.

This summer, I was called to find resources of patience with the kids that I didn’t know I had. I was called to find energy and enthusiasm to make each day fresh and new. I was called to reconcile conflicts that I struggled to identify with and understand. And much of the time, I didn’t succeed at these things. But remembering to live gratefully in God’s house was a source upon which I could rely to see and care for the kids and leaders more clearly and more carefully. Living in God’s house—in touch with the Holy Spirit—allows us to be in touch with God’s unconditional love and the seeds of unconditional love in ourselves. When we are aware of God’s unending love for us, we begin to see God in other people and appreciate them in their highest potential.

Let me offer you another example. Over the course of the summer, I ended up spending a good portion of my time at Cameron Ventures with one of the kids in my department who really struggled with his anger. I often encountered him fighting with the other kids or physically expressing his frustration on the leaders. Often, together with one of my leaders, I sat him down outside the group and had a conversation with him about his behavior. These conversations were difficult, but they revealed to me that he knew he was struggling with his emotions as much as we were. Moreover, I realized that if I was angry or showed any frustration myself, we wouldn’t be able to move forward. Each day had to be a clean slate, without making judgments about him from his past behavior. And I noticed that when I took the time to remember that God’s house is always here, that the present moment is always here, that each and every person is overflowing with God’s love, we were able to reconcile his behavior and come to a solution. It seemed that when we let ourselves return to God’s house and took refuge there, God took care of the situation in a way that no forcing or extra effort on my part could ever do.

A couple of hours before our Parent’s Night, an annual celebration of the kids and their talents at BYP and Ventures, the same kid stormed out of the room where we were rehearsing and proceeded to shout at me and the leaders. He refused to perform that night and was threatening to break things. It took a long time to reach him, to really communicate with him and have a conversation about why he was so angry. I began to ask him about his anger: where he felt it, what color he thought it was, what shape it had, and other physical qualities of his anger. He said it was a deep, deep red and in the shape of the Devil. He was an exceptionally gifted drummer, so I asked him what the beat of the Devil was. Confused, he said it was just random rhythms, not conforming to a particular beat. Eventually, he worked through his anger and performed with great gusto and enthusiasm that night.

However, for me the real miracle came the next day, when he came running up to me with a big smile on his face, saying, “

I feel exceptionally fortunate to have spent the summer at Cameron House, and to have become familiar with a Christian community, one that is welcoming, vibrant, and socially engaged. And I am thankful to have worked and grown together with a wonderful group of kids and leaders. Most of all, however, I am grateful that God’s house opens its doors every moment of every day, that peace and transformation are indeed possible, and that the Holy Spirit can be present in our lives. May the peace of Christ be with us and may God’s house always be our refuge and our strength. Amen.

Blog Archive

-

▼

2005

(78)

-

▼

August

(22)

- High-Context, Low-Context

- A Breath of Fresh Air

- New and Depressing Things

- One-string Wonder

- Settled In

- A Successful Session

- Four Masters

- A Change in Pace

- A Restful Change in Plans

- Conversation and Collage

- Wat Ummalom and Wat Phnom

- CLA Studio

- Tropical Fruit and Syllabic Writing

- Greetings from Phnom Penh!

- Tran Quoc Pagoda, Part 2

- Tran Quoc Pagoda, Part 1

- Four Pagodas in Saigon

- Good Morning, Vietnam

- Beautiful Clouds in Korea

- And He's Off

- Last Ride on BART

- Living in God's House

-

▼

August

(22)

Links

- Access to Insight

- Buddhist Community at Stanford

- Cambodian Living Arts

- Erik W. Davis

- Southeast Asian Service Leadership Network

- Rev. Danny Fisher

- All content © Trent Walker 2005-2010. All rights reserved. You are welcome to use content here with attribution for non-commercial purposes, provided the content itself is not altered.