The "lake" in the background is actually flooded farmland (rice fields). Many of the provinces surrounding Phnom Penh receive this kind of flooding during the monsoon season.

Reflections on Cambodia, Buddhism and Music

Today Rith, my language teacher, and I went visit Wat Ang Krapeu, a popular pagoda during the Buddhist holiday of Pchum Ben. Together with Rith's extended family and friends (about 15 people), we traveled for about hour outside of Phnom Penh to visit this wat, which in the rainy monsoon season is mostly surrounded by water stretching out to the distant hills. The name of Wat Ang Krapeu refers to the crocodiles (krapeu is Khmer for crocodile) that used to live in the area.

Today Rith, my language teacher, and I went visit Wat Ang Krapeu, a popular pagoda during the Buddhist holiday of Pchum Ben. Together with Rith's extended family and friends (about 15 people), we traveled for about hour outside of Phnom Penh to visit this wat, which in the rainy monsoon season is mostly surrounded by water stretching out to the distant hills. The name of Wat Ang Krapeu refers to the crocodiles (krapeu is Khmer for crocodile) that used to live in the area.

I've been spending a good deal of my time at my desk recently. I feel very fortunate to have the time to study this month. Studying Khmer is always fulfilling and the results are always quite tangible, but it is also just as compelling for me to read about new research in Cambodian Buddhism and then go out to local wat and observe what I have read about firsthand. I am very excited to be able to do some reseach of my own over the next couple of months.

I have also started working on transcribing some recorded smoat music and reading some translations of the chants. In order to really learn the music I will also need to know the meaning of the words, which are both in Khmer and Pali (an ancient Indian language). So while I have a good deal of work to look forward to, I am grateful that this kind of work is very fulfilling for me. And the music is all around me. When I walk through the streets and pass by a funeral, the smoat music, made even more eerie by the fact that is played on cassette tapes that have been copied way too many times, echoes between the building. And because I live across the street from a wat, if I rise at 4:30 AM (well worth it), I can hear both the chanting of the monks and live smoat chanting, because the Pchum Ben fesitival is currently taking place. Every hour of every day there is an opportunity to learn something new.

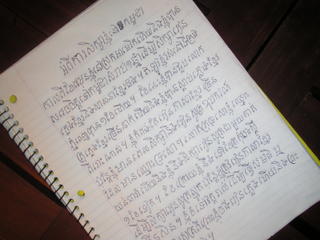

Silapak Khmer Amatak (SKA or Cambodian Living Arts) has asked me to write monthly updates of my progress. I wrote a first draft in Khmer (above), but when I finish a longer (and more gramatically correct) version in English, I'll post it here.

When I realized that I was going to live in a Buddhist country for one year, I wasn't entirely sure what to expect. I knew the statistics, to some extent: 95% of the country's population is Theravada Buddhist, the rest mostly from historically Muslim ethnic groups or Khmers who have converted to Christianity. And I knew that a large percentage of Khmer men have been, are or will be monks for a period in their lives, although this percentage is much smaller than in pre-revolutionary times. Moreover, I knew I was going to encounter a large discontunity between the scriptural teachings of the Buddha--his message of rational inquiry, meditation, and liberation from suffering--and the actual practice of Buddhism in Cambodia. But on the whole I was unprepared for the forms of Buddhism and religious practice I have encounted so far. In America I became closely acquainted with two Buddhist communities, both nominally from the Sino-Japanese tradition of Mahayana Zen Buddhism. While one stressed community life and rigorous meditation and the other put an emphasis on devotional chanting, they both essentially came from the same roots. Mahayana Buddhism, practiced in Vietnam, China, Korea, Japan, Mongolia, Tibet, and Bhutan, developed about 500 years after the death of the Buddha as a reaction to the tendency of Buddhist monastics to pay attention only to themselves and not to the wider community. Mahayana scriptures thus emphasize compassion and the ideal of dedicating one's life to the service of others. There are many more philosophical differences as well, but I think they are easy to stress too much. In truth, there is not that much difference between the two branches, especially at the level of everyday practice, and much progress has been made in the twentieth century to bring to the two schools back together. Nevertheless, Theravada Buddhism emerged in a different cultural context than the Mahayana, so I am still a little lost when I walk into a Cambodian wat. The chanting, the bowing, the symbols, and the cultural traditionsare still mostly unknown to me. Whereas in Vietnam it was easy for me to feel comfortable and at ease in the temples, I am still a bit bewildered by the wats I have been to. However, At the level of monastic discipline, there is very little significant difference between the two branches, and so I expected at least this to be similar in Cambodia to what I had seen in America. At one temple I became familiar with in San Francisco, the seven resident nuns maintained a strict observation of the Buddhist vinaya, the texts that detail the rules of monastic comportment. The nuns rise at 3:30 AM, meditate for several hours before beginning work around the temple after dawn, eat one meal a day before noon, and then work, study, and meditate until late in the evening, when they sleep sitting up in the lotus position until early the next day. The nuns always maintained a meditative atmosphere in temple, treated everyone with respect and quiet dignity. This kind of discipline is specifically outlined in Buddhist texts, and was advocated by the Buddha as providing a helpful structure to community life. I do not generally making judgments about others whom I do not really know, but the discipline of the monks in Cambodia really suprises me. I am not used to seeing monks smoking, handling money, or chatting online. Of course, these are small things, but the discipline of the sangha as a whole does not seem to lend itself to the primary intention of Buddha's teaching, which is the release from attachment and suffering. One possible reason for this is that most young men who enter the monkhood have no intention of studying and teaching dhamma for their whole lives. Some are monks for very brief periods as a way to honor their parents, some are seeking to escape from drug addiction or alcoholism, and still others are looking for a secular education to prepare them for a business career. There is nothing wrong with any of these reasons, and I don't want to criticize them, but they frankly have nothing to do with the Buddha's essential message of rational inquiry, meditation, and liberation. The Cambodian sangha suffered a tremedous blow during the Khmer Rouge period, and over 80% of the monks living in Cambodia in 1975 died before 1980. So the sangha that did survive was one that was fractured and much smaller before, and without a doubt some of the continuity, traditions past down orally over 2,500 years, was lost. This again explains much of the state of the sangha today. When Ratanak and I were visiting Angkor Wat, as a monk and another young man passed by us I heard a "rubber ducky" sound. I chuckled a little at hearing this quirky, quacky sound at a place as solemn as Angkor Wat, but Ratanak was clearly quite upset. She explained that monks are not supposed to behave like that (i.e. have a plastic squeaky toy under there robes as way to amuse themselves), and that she gets upset when she sees monks who aren't really interested in the monastic life (i.e. men who just want to say they are monks and get respected by others, but who still talk to their girlfriends on their cellphonesat night). For me, I was not really upset, because as a non-Khmer, I haven't grown up with the same feelings of reverence toward the sangha. But it did make me realize that many Cambodians are also not content about the discipline of the monks they support. Of course, I do not mean to say that all the monks in Cambodia lack discipline; this is far from the truth. And they are all certainly more disciplined that I am as a layperson. I have met monks and visited wats where discipline is strong and alive and in whom I can sense the original teachings of the Buddha--to me this is very inspiring and moving to witness. |