Reflections on Cambodia, Buddhism and Music

Saturday, November 26, 2005

Queen Maya's Lamentation

The name of the song is, in an English transciption of the Khmer, "Tumnuonh Neang Sere Moha Maya." An appropriate English translation would be "Lamentation of Queen Maya."

The context of this song is similar to other smote pieces, in that it used primarily in funeral ceremonies, particularly when a sick person is on verge of death. Smote songs, which recount Buddhist teachings or stories in poetic form, are used to direct the mind of the dying person towards the Buddhist trinity, or Three Jewels: the Buddha, his teaching, and his disciples, so that they will be reborn in a favorable realm. This particular ceremony is called samwek, and this particular song is one of many that can be used for that occasion, to be sung by either monks or laypeople.

The content of the song is centered around the Buddha's mother, Queen Maya, lamentation for her son, who has left the palace where he was a prince and heir to the throne, gone deep into forest, and taken up extreme austerities, including eating very little food, in order to reach enlightenment. The Buddha later realized the futility of his efforts and accepted food in order to nourish his body and mind, after which he finally attained enlightenment. Before this, however, he became extremely thin and weak, to the point that he was practically only skin and bones, and the shape his backbone became visible from the front. Queen Maya, having died only seven days after his birth, is told by her fellow gods in the realms of heaven that her son, now in his thirties, has become very weak and emaciated. It is at this point that she begins her lament.

This particular song is closely related to another that I have been studying, called "Bandam Neang Moha Maya Devi Jampuah Neang Goutamei," or "The Admontions of the Buddha's Mother Maya for Lady Gotami." A translation of this song follows below the translation of "Lamentation of Queen Maya."

Lamentation of Queen Maya (Tumnuonh Neang Sere Moha Maya)

O my son, my dear son!

You have become so thin and weak.

And your mother feels great sorrow for you,

Sorrow that exceeds all comparison.

O my child, seven days after your birth,

Your mother suddenly passed from this world,

And ascended to the highest realms of heaven,

Where she now resides with the gods.

I, your mother have heard from the gods

That you, my child, were born into a beautiful body,

Magnificent in form and free from disgrace.

So now why have you become so emaciated?

Your mother has come to see your body, O child!

She feels great sorrow, and her heart

Grows soft with pity to see you like this.

For what reason do you do this, my son?

The Admontions of the Buddha's Mother Maya for Lady Gotami (Bandam Neang Moha Maya Devi Jampuah Neang Goutamei)

"Dear Lady Gotami, o younger sister!

Please remember this advice

That I admonish so strongly on to you.

Please, younger sister, be kind and forgiving to me.

"Elder sister gave birth to a beloved son,

Only to live as a his mother for seven days.

Seven days, younger sister!

Death came and blocked my path.

"Sister, this child is remarkable indeed.

Wise sages came to pay respect to him.

His is called Siddartha according to the law.

For the benefit of all living beings,

"Our beloved son will attain enlightenment,

Knowing all paths to salvation by his own effort.

Many will come to ask for his help,

Granting abundant happiness to humans and gods alike.

"Younger sister! Please be determined

And have compassion for this child.

Let him suckle at your breast

And care for him with your own hands.

"Sister, don’t lost your fortitude

And call on servants to care for him.

Raise him with your own strong arms

And know that this is true love."

Having finished giving her admonitions,

She passed away and her life was finished,

To be reborn in the Tusita heaven,

Resplendent in numberless colors and powers.

The reason that Queen Maya was born

In the blissful Heaven of the Thirty-three,

Is that many gods there could inform her

About the exceeding virtue of her beloved son.

There came a time when the Buddha

Wandered back and forth across a stretch of forest

Staying for four reasons

In the Uruvela forest in the city of Gaya.

His body grew emaciated till his bones poked through,

His eyes grew bleary, wide-open beyond description,

As he collapsed down to the earth,

Enduring terrible suffering but still alive.

At that time the beautiful Queen Maya

Descended from paradise to come take a look

At the body of the Blessed One.

I humbly now finish this poem.

Friday, November 25, 2005

Written Culture

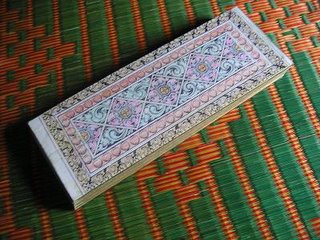

and opened in a concertina arrangement, rather like an accordion.

Inside the book were hand-written texts for the smote songs most often used at funeral ceremonies,

Inside the book were hand-written texts for the smote songs most often used at funeral ceremonies,

written in unfailingly beautiful Khmer script.

He later explained that this sort of manuscript was called a krang. We then began to study some the smote songs contained within. After doing some more research on the subject, I found out some more information on the history of this kind and other kinds manuscripts in Cambodia.

The history of written culture in Cambodia begins with the history of Buddhist scriptures. The teachings of the Buddha were passed down orally for about five hundred years before monks began to start writing them down on palm leaves. This tradition of palm-leaf manuscripts came to Cambodia with the spread of Buddhism, especially with the conversion of the kingdom to the Theravada branch of the religion in the 13th century. Khmer palm-leaf manuscripts were mainly used in wats to be studied and recited by the monks. Mostly written in Khmer script representing the sounds of the Pali language, palm-leaf manuscripts are difficult to handle and to study, and reading them is an art in itself. Thus the Khmer script used in the manuscripts came to be associated with mystical powers, and many rituals developed around the their use. Palm-leaf manuscripts do not last very long, and today very few Cambodian manuscripts remain from before the 19th century. They were regularly burned as a way of making merit and then recopied onto new leaves. This tradition survived as the main method of recording Buddhist scriptures and literature well in the 19th century.

The krang developed later than the palm-leaf manuscripts, but has also been a traditional method of storing Buddhist scriptures throughout Asia. Most temples in China and Japan have collections of this kind of manuscript, both for ritual use and for study. In Cambodia, krang are produced on paper made from mulberry leaves, hand-written in ink, and then bound in a folding arrangement. They generally last longer than palm-leaf manuscripts but are nearly as difficult to produce, as no printing technology is used.

With the onset of the French protectorate in Cambodian in the late 19th century, as well as the influence of reformed Siamese Buddhism from Thailand, the culture of palm-leaf and other manuscripts in Cambodia began to change. In order to increase their control over the Buddhist clergy, the French colonial government establised the Buddhist Institute in the early part of the 20th century. The Buddhist Institute set about to produce a complete translation of the Tripitaka (the corpus of Buddhist scriptures) in Khmer, at a time when most temples in Cambodia lacked even a complete Pali version of the scriptures. The was initially much resistance to the move away from hand-written manuscripts among traditionalist monks, who sensed a magic power in the ancient Khmer letters and the rituals associated with them and therefore feared a change in how the teachings of the Buddha were respected. However, although there are monks who still use the palm-leaf manuscripts, serious monastic students more often used printed literature to understand the words of the Buddha. The Buddhist Institute also printed the first Cambodian dictionary, under the leadership of Buddhist patriarch Chuon Nath, which is still the only Cambodian dictionary in use today, to my knowledge. Most importantly, the Buddhist Institure made possible the advent of print culture in Cambodia, and they have printed many hundreds of small and large volumes alike on Buddhism and traditional literature over the past seventy years. Thus most Buddhist education has changed from being focused on palm-leaf or krang manuscripts to printed books.

Today, printed books are available very cheaply in Cambodia, usually starting from around 25 cents. This is because most of the titles, both foreign and domestic, are photocopied from the original publications. Some would caracterize Cambodia as not being a very literary culture, although I would argue that this is not the case. Traditional literature is, however, to some extent endangered in Cambodia, like some many other traditional arts forms. Furthermore, the traditional manuscripts may be lost if efforts are undertaken to preserve them.

For me, it's really an honor and a wonderful opportunity to be able to study smote from the krang manuscripts and learn about the care and effort that had to go into each word before the advent of printing in Cambodia. As of late, I have been learning to type in Khmer, which is a rather slow and cumbersome process, in order to record some of the smote texts found in the manuscripts and in other sources. Even if typing now seems slow, it is fascinating to think about how much the culture around written texts in Cambodia has changed over the past one hundred years.

Thursday, November 24, 2005

Three-Month Report

From one perspective, I really have no idea how much my Khmer has progressed, as not being a native speaker, I have no ear for whether my accent is reasonably acceptable or if my grammar accords with modern conventions or not. However, I do know that my language skills have improved somewhat since last month, particularly in the areas of reading and listening. As I have been focusing most of my attention on the literary, Pali-laden Khmer that smote songs employ, most of my progress has been in understanding this particular style. For the most part, I am able to read texts of smote songs and understand what they are about, and with the aid of a dictionary, I can produce a reasonably coherent translation. At this point, I have stopped taking language lessons, and I notice that my speaking and writing skills, in particular, are falling behind. The smote masters obviously simplify their language when they speak with me, so I can usually understand what they are saying without difficult. Nevertheless, when it comes time to respond to them, I am often lost for words. I hope that I will have more chances to work on this.

I have been continuing my study of the tro sao, and I generally find time to practice the eight songs I have learned so far. However, my teacher Yun Theara has been, understandably so, very busy, and I have only been able to study with him on an occasional basis, about every two weeks. I have really enjoyed my studies so far, and have had some chances to share some Mahaori songs with the people in Ka Yeaw village, where I am staying in Kompong Speu.

Additionally, I have also had the opportunity to spend a good deal of time researching Khmer Buddhism, and more specifically the literature associated with Theravada Buddhist funeral rites. I have had a few chances to do relatively independent research in the past, but this is the first time that I really had no idea what I would find over the course of my research. At this point, I have identified most of the relevant English and French language material on Khmer Buddhist rituals and literature and am presently in the process of reading, rereading and taking notes on these sources. I also searching for Khmer-language sources, which has been very rewarding, and I look forward to discovering more useful texts through this process.

Now on my third week in the countryside, I am realizing the challenges of studying smote. Once I translate a particular text into English and have a clear idea of its content, I find that it is not too difficult to memorize the Khmer words, although the length of the songs certainly requires that memorization takes a significant time commitment on my part. The melodies also stretch my musical capabilities as their freedom from Western standards of rhythm and meter makes them very difficult to transcribe accurately. However, the hardest part about learning smote songs for me is pronouncing Khmer words correctly. Certain sounds in the Khmer language are very difficult for me to pronounce clearly, and I know that I will continue to struggle with these sounds as I continue my study. I am very grateful that the masters are patient enough to accommodate for my deficiencies.

As for the coming months, I have a clear idea of what path my research and writing will take. I hope that I will soon be able to find a mentor for this project, a process that should give me more direction and point out some of the many gaps and oversights in my research. I am less sure, however, about the actual study of smote. Some of the more difficult songs reportedly take months to learn, and while my pace of learning may be different, I do not have high expectations for learning more than a handful of smote songs. In my view, learning just a few songs well will be ultimately more important, to both my research and my understanding of the art more.

At the urging of my teacher Proum Uth, I have begun to study the Pali and Khmer chants used in the novice ordination ceremony. Although he recommended this course of study in order to prepare me for the monkhood, the study of Pali chants, in particular, is helping me with the pronunciation of the regular Khmer smote songs, as well as teaching me about the Pali chants used in the funeral ceremonies of which smote is a part.

Overall, I am very happy to have come to this point after three months here and I am especially grateful to have met so many people who were so willing to help me in surprising and wonderful ways. I am cautious in terms of my expectations for myself, and I hope that in the coming weeks I am able to find more direction and sense of purpose for my studies here.

Friday, November 18, 2005

Water Festival

This past week was the Water Festival in Phnom Penh, a three-day event which usually draws almost two million people from the countryside to come to the capital, which normally has a population between one and two million, depending on how the city limits are defined. I only spent a little time in Phnom Penh during the festival, as it is quite a chaotic and crowded event. At night, particularly, the streets near the water front and major parks are packed with people, and it is difficult to move. But for many Cambodians, especially those who come from the countryside, it is a wonderful event and a celebration of national pride. The boat races are the highlight of the event, with long boats (see photo above) competing head-to-head in the Tonle Sap river.

However, the countryside has its own version of the Water Festival that is equally special. Most provinces have their own boat races, but to me the most interesting part comes during the evening. The ambok (raw, unhusked rice that is crushed flat and roasted) ritual usually takes place well after the sun has set, during the night of the full moon which occurs during the three days of the water festival. The ceremony is nearly identical to that which takes place concurrently in the royal palace. The royal ceremony, ostenstibly Brahmanstic (Hindu), has mnay animistic elements as the essential purpose is predicting and petitioning for good rainfall in the coming year. However, the full moon night is also significant in Buddhism, as it is the time when monks and laypeople renew their vows to lead upright and virtuous lives.

Above is the table where food offerings are made, including bananas, coconuts, sugar cane, and ambok. The food will later be mixed together and eaten--it's quite delicious!

Because of the full moon night, Buddhist Pali chants are recited along with the animistic petitions for rain.

Because of the full moon night, Buddhist Pali chants are recited along with the animistic petitions for rain.

The three candles on the top of the wood frame represent three districts in Kompong Speu province. They were later allowed to drip thier melting wax onto the large banana leaves as a way of predicting the amount of rainfall in each district. I was very glad that I was able to witness and participate in this event and see the whole village come together, revealing many more aspects of Khmer culture than I ever would have been able to see in Phnom Penh or read in a book.

Thursday, November 17, 2005

Ka Yew Village

The house where I am staying.

The "spirit house" that serves as altar to tutelary spirits (neak ta)

Teng, one of Proum Uth's sons and Proum Uth's wife.

One of Proum Uth's daughters.

Pakdey, Proum Uth's youngest son, and me.

A neighbor and his beautiful cow.

A happy neighboring family.

Monday, November 14, 2005

L'apprentissage des langues

Quand j'ai decidé d'étudier le français, je n'étais pas tellement sûr que je pourrais utiliser cette langue à l'avenir. Cependant, j'adorais le son du français, et donc j'étais bien heureux de l'apprendre. Après avoir obtenu mon diplôme, je me suis étonné si je ne parlerais le français plus jamais. Au lycée, je me suis amusé en lisant des livres en français en dehors de la classe. Mais je savais que si je ne parlais point, ma facilité vis-à-vis le français irait se perdre tout à coup! Ainsi j'ai pensé, "pourquoi ai-je l'étudié? Quels sont les bienfaits de mon travail?"

Sunday, November 13, 2005

Life in the countryside

When I arrived, I had the impression that almost everyone in the village (about sixty families) knew about me before my arrival. I am staying with the family of Proum Uth, the smote master who teaches a class near a wat on a small hill a few kilometers from the village. As Proum Uth spends the first half of each month as a achar in a wat in Kandal province, only his wife and two of his sons where living at the house when I arrived.

The house is situated on the edge of a rice field on the outer portion of the village. Like most Khmer houses, it is "on stilts," in that it sits on raised pillars to create a shaded area underneath where the family spends most of their time. The upstairs area has one room where the family sleeps, and food is prepared in a separate room attached to the house at ground level.

Electricity exists only in the form of batteries, and water used for bathing and cooking is collected in large jars. Water for drinking is boiled in the form of tea, and heat for cooked is generally firewood. I brought along a cheap gas stove, but it blew up (fortunately no one was nearby!). This makes me believe that firewood may be a little safer!

Shortly after I arrived, the two brothers took me meet some of their neighbors in the village. In general, people in Cambodian villages have a good deal of free time each day, and they tend to spend most of it visiting their neighbors or their family (who also may be their neighbors). Wherever I went, the local people always wanted me to try a new kind of fruit or vegetable. After several hours of this, I was feeling rather full but also delighted to meet so many kind and welcoming people.

The two sons, Teng, 19 and Pakdey,17, are currently studying English and other subjects at local schools in preparation for their high school graduation examinations. Pakdey is also a student in the smote class, which meets daily during the week from 4:00 PM to 6:00 PM. They are like brothers to me in many ways, and I am really enjoying being able to spend time with them. Occassionly I go to the local English to help the students there. As there are no foreign teachers there, even a relatively inexperienced teacher can fill a large gap in their English education: pronounciation and proper grammar. I probably will continue to spend a hour a day helping out there or at other schools in the area. In the evening, I am also able to help Teng and Pakdey with their homework. From my point of view, this is the least I can do for them, for not only does Pakdey help me with smote songs, but the whole family, according to Khmer tradition, does not permit me to help very much with the housework, so I am happy that I can help them in other ways.

I will post more about the smote class itself a little later, but I am really happy to finally start studying this form of religious music. I feel truly fortunate to have this opportunity, and while I know it will be a challenge for me, every aspect of smote --contextual, textual, musical, and spiritual-- is fascinating to me.

As I'm writing this, I'm in Phnom Penh, looking out a window to the Tonle Sap river, where 30-meter rowboats, holding sixty or seventy strong rowers are practicing in preparation for the Water Festival, which will take place here over the next three days. Hundreds of thousands of people come from all over Cambodia for this event, and it makes the already apparent chaos of Phnom Penh that much more acute. It's exciting, for sure, but I hope I can sneek back to the quiet of the countryside before the festival ends.

O Ananda!

I recently returned to Phnom Penh after my first week living in the countryside. I do have pictures, but I am unable to post them at the moment because I forgot the USB cable in Kompong Speu. I will also post more later about my experiences in the countryside, but in this post I will share a little more about smote.

The following is a translation and transliteration of a smote song called "Pacchimbuddhavacanak." The song is sung from the perspective of the Buddha as he is dying. Ananda was the Buddha's faithful attendant throughout his teaching career and was known for his remarkable memory; indeed, it is said that he had memorized every one of his teacher's sermons. Considering that the oral teachings of the Buddha fill over forty volumes of text, this is an impressive feat.

The Buddha referred to himself as "the Tathagata," which means "the one who comes from suchness". Tathagata could also be translated as "coming from nowhere, going nowhere". He used this appellation to emphasize his realization that living beings do have separate souls or selves and eventually return to emptiness.

This song, like all smote songs, is actually more of a poem set to a standard melody. The poem can be recited as well as sung. Each stanza consists of four lines, and the metric pattern for each stanza is five syllables, six syllables, five, six. The rhyme scheme is such that that the last syllable of the second and third lines of each stanza rhyme with the last syllable of the fourth line of the preceeding stanza. The last syllable of the first line of each stanza also rhymes will the third syllable of the second line of each stanza.

The translation does not reflect the meter or rhyme scheme, but the transliteration of the Khmer which follows the translation should make this more clear. Because smote songs often contain many Pali words (e.g. Tathagata, Ananda), I have chosen to use a transliteration system that reflects the standard way of Pali romanization, so that the Pali roots are more clear, although much phonetic representation is lost. For example, "Tathagata" is transliterated as "tathāgat," but the actual Khmer pronounciation is closer to "dahk-ta-koot."

As the most common context of smote is a funeral ceremony, this particular song is representative of many works in the genre, as it recalls the deathbed of the Buddha himself. It is also typical in its recounting of a famous Buddhist story, its frequent use of Pali words, its poetic meter, and its lamenting tone charged with exhortations to practice Buddhist teachings.

O Ananda, do not delay!

Come here immediately,

For the Tathagata will pass away.

Abandon yourself without fail.

Please dwell in happiness.

Do not be miserable, dear friend!

The Tathagata will now depart

Do not grieve, O Ananda!

Within the body of the Tathagata

The five aggregates will all be extinguished.

Please stay, O Ananda!

Try to look deeply into your body.

Every day your body

Is like a fragile plate.

It does not last long

And will surely be destroyed.

For this reason, Ananda,

Please reflect deeply,

Not about the passing of the Tathagata,

But about your own salvation.

The teaching of the Tathagata

Will surely last long

And whoever has a pure mind

Can practice the path accordingly.

Now the Tathagata

Will be extinguished in Nirvana.

Old age moves in by force,

Crushing and cutting off all life.

yo vo ānand 'aoey

nae pā 'aoey mak 'āy rā

tathāgat niṅ maranā

câk col pā min khan ḷoey

cūr pā nau 'auy sukh

kuṃ jā dukkh ṇā pā 'aoey

tathāgat lā pā hoey

kuṃ sok loey ṇā ānand

aṅg añ tathāgat

niṅ ram lát 'ás pañcakkhanth

nau cuḥ nā ānand

khaṃ gne gnân knuṅ aṅg prāṇ

kluan 'anak nau sabv thṅai

mān upameyy ṭūc jā cān

min shtit ster punmān

guṇ niṅ pān vinās dau

hetu neḥ pān ānand

cūr gne gnân git 'auy jrau

it bī tathāgat dau

'anak eṅ nau thae sāsanā

sāsanā tathāgat

sthit prākat niṅ 'anak ṇā

ṭael mān citt jrah thlā

prabrẏtt truv tām laṃ 'ān

grā neḥ tathāgat

niṅ raṃ lát khanthanibbān

ṭoy jarā cūl ruk rān

dandrān mak phtâc saṅkhār

Monday, November 07, 2005

Moving Out

As I will not have internet access in the countryside, or electricity, running water or refridgeration for that matter, I will be able to update this site only on a weekly basis, as I currently plan to return to Phnom Penh on weekends in order to continue study on the tro sau instrument. As my path of research unfolds, I am also finding more and more books and documents in the Buddhist Institute and in other libraries that are relevant to my study of smote chanting, so I also plan to be using these resources when I return to Phnom Penh periodically. I must admit that I miss going to school, and I am getting really excited about my research here. I hope I will be able to post more about it here in the future.

Links

- Access to Insight

- Buddhist Community at Stanford

- Cambodian Living Arts

- Erik W. Davis

- Southeast Asian Service Leadership Network

- Rev. Danny Fisher

- All content © Trent Walker 2005-2010. All rights reserved. You are welcome to use content here with attribution for non-commercial purposes, provided the content itself is not altered.