and opened in a concertina arrangement, rather like an accordion.

Inside the book were hand-written texts for the smote songs most often used at funeral ceremonies,

Inside the book were hand-written texts for the smote songs most often used at funeral ceremonies,

written in unfailingly beautiful Khmer script.

He later explained that this sort of manuscript was called a krang. We then began to study some the smote songs contained within. After doing some more research on the subject, I found out some more information on the history of this kind and other kinds manuscripts in Cambodia.

The history of written culture in Cambodia begins with the history of Buddhist scriptures. The teachings of the Buddha were passed down orally for about five hundred years before monks began to start writing them down on palm leaves. This tradition of palm-leaf manuscripts came to Cambodia with the spread of Buddhism, especially with the conversion of the kingdom to the Theravada branch of the religion in the 13th century. Khmer palm-leaf manuscripts were mainly used in wats to be studied and recited by the monks. Mostly written in Khmer script representing the sounds of the Pali language, palm-leaf manuscripts are difficult to handle and to study, and reading them is an art in itself. Thus the Khmer script used in the manuscripts came to be associated with mystical powers, and many rituals developed around the their use. Palm-leaf manuscripts do not last very long, and today very few Cambodian manuscripts remain from before the 19th century. They were regularly burned as a way of making merit and then recopied onto new leaves. This tradition survived as the main method of recording Buddhist scriptures and literature well in the 19th century.

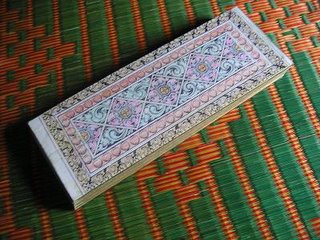

The krang developed later than the palm-leaf manuscripts, but has also been a traditional method of storing Buddhist scriptures throughout Asia. Most temples in China and Japan have collections of this kind of manuscript, both for ritual use and for study. In Cambodia, krang are produced on paper made from mulberry leaves, hand-written in ink, and then bound in a folding arrangement. They generally last longer than palm-leaf manuscripts but are nearly as difficult to produce, as no printing technology is used.

With the onset of the French protectorate in Cambodian in the late 19th century, as well as the influence of reformed Siamese Buddhism from Thailand, the culture of palm-leaf and other manuscripts in Cambodia began to change. In order to increase their control over the Buddhist clergy, the French colonial government establised the Buddhist Institute in the early part of the 20th century. The Buddhist Institute set about to produce a complete translation of the Tripitaka (the corpus of Buddhist scriptures) in Khmer, at a time when most temples in Cambodia lacked even a complete Pali version of the scriptures. The was initially much resistance to the move away from hand-written manuscripts among traditionalist monks, who sensed a magic power in the ancient Khmer letters and the rituals associated with them and therefore feared a change in how the teachings of the Buddha were respected. However, although there are monks who still use the palm-leaf manuscripts, serious monastic students more often used printed literature to understand the words of the Buddha. The Buddhist Institute also printed the first Cambodian dictionary, under the leadership of Buddhist patriarch Chuon Nath, which is still the only Cambodian dictionary in use today, to my knowledge. Most importantly, the Buddhist Institure made possible the advent of print culture in Cambodia, and they have printed many hundreds of small and large volumes alike on Buddhism and traditional literature over the past seventy years. Thus most Buddhist education has changed from being focused on palm-leaf or krang manuscripts to printed books.

Today, printed books are available very cheaply in Cambodia, usually starting from around 25 cents. This is because most of the titles, both foreign and domestic, are photocopied from the original publications. Some would caracterize Cambodia as not being a very literary culture, although I would argue that this is not the case. Traditional literature is, however, to some extent endangered in Cambodia, like some many other traditional arts forms. Furthermore, the traditional manuscripts may be lost if efforts are undertaken to preserve them.

For me, it's really an honor and a wonderful opportunity to be able to study smote from the krang manuscripts and learn about the care and effort that had to go into each word before the advent of printing in Cambodia. As of late, I have been learning to type in Khmer, which is a rather slow and cumbersome process, in order to record some of the smote texts found in the manuscripts and in other sources. Even if typing now seems slow, it is fascinating to think about how much the culture around written texts in Cambodia has changed over the past one hundred years.

No comments:

Post a Comment